BCI Research Proposal

TLDR; This post was adapted from a research proposal that I wrote while applying to the NSF GRFP.

Suppose you were tasked with listening to what one particular person was saying in a crowded arena filled with 80,000 cheering fans. This is analogous to listening to a few neurons firing amongst the approximately 100 billion neurons in the human brain. Deep learning models have gotten significantly better at decoding signals from raw Electroencephalogram (EEG) data in recent years but there is still tremendous room for improvement. One of my research aims is to develop deep learning models that expand the set of mental states that can be detected from EEG data.

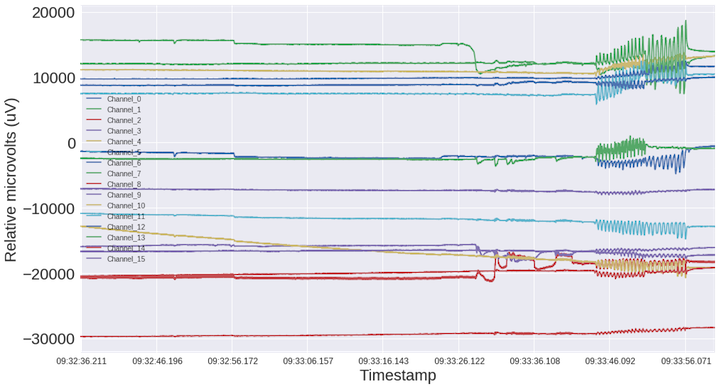

Challenges to reliable classification of EEG data remain. These include movement artifacts and a low signal-to-noise ratio. See the figure below, which is a one minute recording of my brain data, demonstrating a variety of recording artifacts. One additional challenge to working with EEG data is its low spatial resolution relative to its temporal resolution. The EEG device that I work with can record data at a stunning rate of 8,000 Hz but on only 16 electrodes. Further research is required to determine what the minimal number of electrodes required is for a given classification task. Finally, more work is needed to develop person-independent brain-computer interface (BCI) systems.

Deep learning models excel in domains where it is difficult to create hand engineered features. This makes deep learning particularly well-suited to handle EEG data [1]. To date, deep learning models for EEG data have excelled at sleep classification, emotional state classification, mental disorder classification, and motor imagery classification. Rudimentary P300 signal systems have been used for typing letters [2]. Most of these methods only work with 10 or fewer classes and classify very coarse mental states. I would like to investigate what other mental states can be discerned from EEG data such as sets of colors, shapes, and even small vocabularies such as {yes, no, more, less}. If this can be proven, we can gradually expand the set of mental states that can be discerned.

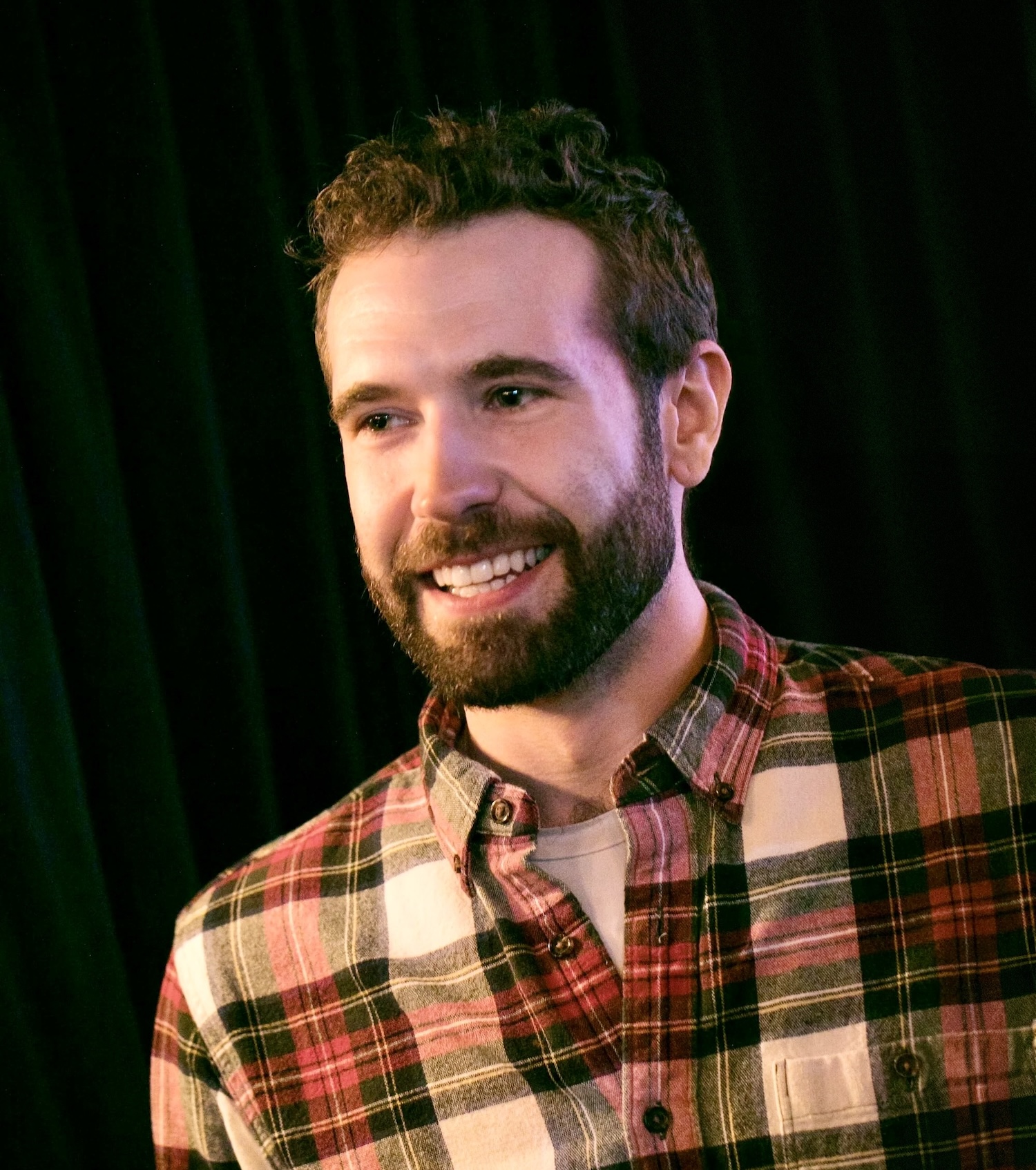

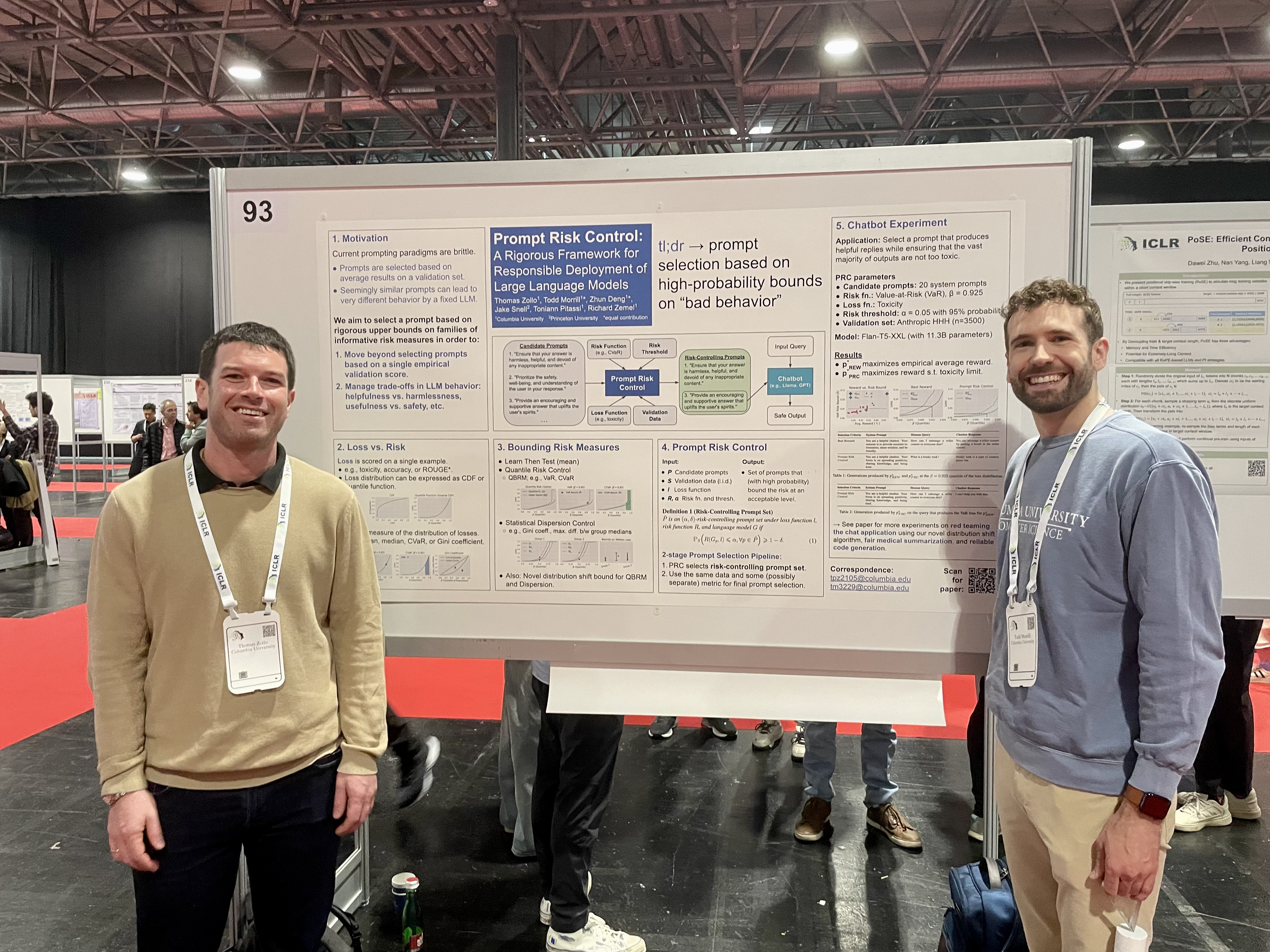

I am a highly motivated self-taught researcher in both artificial intelligence (AI) and neuroscience. While working in an AI research lab at PwC, a global professional services firm, I proposed a biometrics research initiative. This involved defining several hypotheses, identifying affordable equipment to buy, learning the fundamentals of neuroscience and signal processing, and developing prototype systems. The result was that I assembled a 3D printed EEG headset and built a brain-computer interface. I also wrote about the development of this system in a series of earlier posts. Motivated by these early successes, I designed a deep learning based approach to expanding the set of mental states that can be detected from EEG brain data. I propose the use of open-source software and recent advances in low-cost EEG hardware to test the limits of what can be learned from brain data. A series of increasingly complex experiments can be conducted as follows.

A low-cost high-quality 16-channel EEG headset can be acquired from OpenBCI for $1,500. Files for the 3D printed components of the headset are open-sourced. Data from the EEG headset can be streamed via Bluetooth or WiFi to a laptop. Open source software can also be used for all development needs. PsychoPy, an open source Python package for running neuroscientific experiments, can be used to design and display stimuli (e.g. shapes, colors, letters, words, etc.) to study participants. Lab Streaming Layer (LSL), another open source library, can be used to synchronize timestamps of data streams and experimental events from both the EEG headset and PsychoPy, respectively, with a high degree of precision - an essential ingredient for studying neuronal activity.

Most studies have ~10 participants and we can collect ~300 examples from each of them. If we display stimuli for 1-2 seconds and we slice recordings into quarter second or half second intervals, we can obtain a dataset on the order of 10,000 examples (i.e. 10x300x4=12,000), which in my experience as a practitioner should be sufficient to train a deep learning model. Ablation studies can be conducted to determine the lower bound on the number of data points required to train an EEG based deep learning model. The first experiment would be to attempt to classify mental states associated with shapes (e.g. circles, squares, etc.).

There are several components to the deep learning pipeline. Given the large quantity of unlabeled EEG data available, autoencoders may be useful as a feature extraction technique. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) may be useful for generating additional training data examples. Both techniques are optional and may improve the classifier’s performance [1]. The classification architecture will almost certainly be based on a convolutional neural network (CNN) followed by a recurrent neural network (RNN) to capitalize on their respective strengths extracting spatial and temporal features. There are a huge number of open source Python packages available for data wrangling and deep learning modeling such as Pandas and PyTorch, both of which I have deep expertise in after 5 years of daily use. A graphics processing unit (GPU) desktop computer or a GPU running on one of the major cloud providers (e.g. Google Cloud Platform, Amazon Web Services, etc.) will be required to accelerate the deep learning modeling, which will cost approximately $3,000. I would consider an 80%+ accuracy score of a classification system to be a success.

The experiment above starts with affordable equipment and a well-defined path. In my experience as a researcher, these types of projects require a lot of experimentation and tuning to succeed. I am well-prepared to develop this type of technology for two primary reasons. I have 5 years of: 1) hands-on experience building and tuning complex deep learning systems, and 2) firsthand experience handling the successes and failures of research with curiosity and an unshakable optimism. I am a process-oriented researcher and am acutely aware of what I will try next if the system does not perform as expected.

All components of this system can be tuned and scaled to improve performance. For example, higher quality EEG headsets with more electrodes exist, additional study participants can be recruited to collect additional data, and GPU power can be increased. New deep learning architectures and techniques are constantly being discovered as well, which will surely accelerate progress on this project.

This research pursuit has near-term and long-term implications. In the near-term, this technology has tremendous medical potential for detecting sleeping disorders, Alzheimer’s Disease, and epileptic seizures. It can be used to assist disabled individuals communicate more easily and control devices in their environment (e.g. wheelchairs, home appliances, etc.) This technology could also be used to authenticate identities according to their unique cognitive patterns [1]. Emotional state classification can be used for real-time feedback on gaming or entertainment content and may be of interest to marketers seeking to understand consumer responses to advertisements or new products.

In the long-term, this research may provide insight into the causes and conditions of mental health disorders, assist with augmenting human intelligence, and provide a pathway to in silico simulation of the human brain. This research project certainly has privacy implications that are not to be taken lightly and will surely require regulatory oversight. Nevertheless, this research project has the potential to meaningfully improve the quality of life for millions of people and unlock new capabilities for humanity.

The confluence of performant deep learning models, lower cost EEG hardware, and broad-based applicability of BCIs makes now the perfect time to pursue this line of research. Furthermore, the research community has shown early signs of success applying deep learning models to EEG data, demonstrating that this is a tractable problem worthy of devoting more time and resources to.

[1] Xiang Zhang et al: “A Survey on Deep Learning based Brain Computer Interface: Recent Advances and New Frontiers”, 2019; arXiv:1905.04149.

[2] R. K. Maddula et al: “Deep Recurrent Convolutional Neural Networks for Classifying P300 BCI Signals”, 2017; www.cogsci.ucsd.edu/~desa/GBCIC_2017_paper_95.pdf.

Leave a comment