Knowledge Graph Construction - Named Entity Recognition (NER)

TLDR; I’m exploring how to extract entities from text in an unsupervised fashion.

This post continues from a previous post that introduces knowledge graphs with some motivating examples. Recall that knowledge graphs are made up of entities (i.e. nodes) and relations (i.e. edges). This post addresses entity extraction in order to create the nodes of the graph. This post will build from the Information Extraction chapter from the textbook Speech and Language Processing.

Entity Extraction (i.e. Named Entity Recognition)

In short, entities are a sequence of one or more words that correspond to a useful piece of information such as a person or a place. Named entity recognition is a task that attempts to correctly identify entities in a piece of text.

We can treat entity extraction as a sequence labeling task and use a sequence classifier such as a Maximum Entropy Markov Model (MEMM), Conditional Random Field (CRF) model, or a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model to label tokens. The label set is domain-specific but a news-based named entity recognition (NER) model might tag: {person, organization, location, …}. Here’s an example sentence to illustrate how tokens are labeled. This example is borrowed from Information Extraction and refers to a snippet from a news article about airlines raising their prices.

American Airlines, a unit of AMR Corp., immediately matched the move, spokesman Tim Wagner said. $\to$ $\color{red}{[_{\text{ORG}} \text{American Airlines}]}$, a unit of $\color{red}{[_{\text{ORG}}\text{AMR Corp.}]}$, immediately matched the move, spokesman $\color{red}{[_{\text{PER}} \text{Tim Wagner}]}$ said.

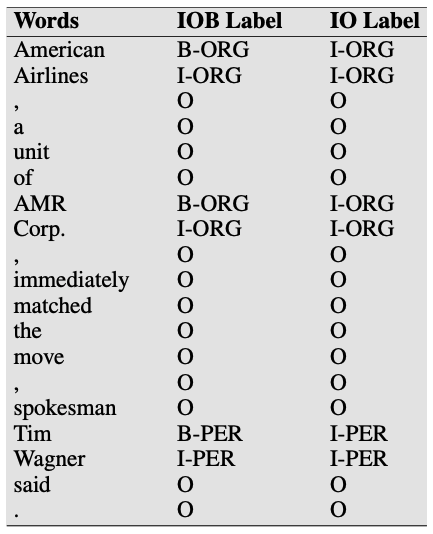

Where ORG corresponds to organization and PER corresponds to person. In particular, each token in the sentence is tagged with beginning (B), inside (I), or outside (O), where tokens tagged with B are the start of an entity, tokens tagged with I are inside the entity (after the beginning token), and tokens tagged with O are outside of any entity. Here’s an IOB representation of the same sentence above. This is the format used for training models.

As with all supervised learning problems, collecting labeled data is where the challenge begins. If you have a domain expert with plenty of time, you can have them read through a sizable sample of the documents in your corpus and develop a labeling methodology as they go. This labeling methodology will include definitions of classes (e.g. {person, organization, location, …}) along with a number of useful examples. It’s best to prioritize the test set first so you have a high confidence set of labels to evaluate against. From there, if the task is simple enough and you want to reduce the time spent by high-cost domain experts, you can ship the task out to a service like Google’s data labeling service to massively scale the size of your training set. I successfully employed this approach while building a domain-specific text classifier. With this labeled set, you can train a sequence classifier to tag entities.

While the above approach is somewhat tried and true, I’m interested in low-effort approaches to collecting training data and building domain-specific models. We may be able to use unsupervised methods to generate candidate entities and have a domain-expert review these candidates in order to formalize a label set. One approach would be to fit a term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) model over the corpus of text and identify important words. You could do this by identifying terms with large TF-IDF scores. You could define the score \(x_i\) for term \(i\) to be the max score over all the documents \(D\). In particular:

\[x_i = \max_{d \in D}(x_{i_d})\]Another definition of the score \(x_i\) for term \(i\) is to compute the L2 Norm of the term’s vector over all documents. In particular:

\[x_i = \sqrt{x_{i_0}^2 + x_{i_1}^2 + \ldots + x_{i_{|D|-1}}^2}\]You could then take the top \(k\) percentile of terms as candidates to be entities or similarly take the top \(n\) terms as candidates, where reasonable values of \(k\) and \(n\) could be tuned against a labeled dataset such as CoNLL 2003.

Another unsupervised approach to generating seed words is latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), which yields important words that correspond to the topics addressed in the text corpus. This approach does requiring setting the number of topics \(m\). Reasonable values of \(m\) can be determined empirically using a labeled dataset such as CoNLL 2003.

Once you have these seed words you can either use the fitted TF-IDF model along with cosine similarity to find similar terms and increase this candidate corpus. Similarly, you could train a Word2vec or fastText model and identify the most similar terms to expand the candidate corpus. At this point, you have two options: 1) work with a domain expert to label some data, or 2) try a fully unsupervised approach.

In the former case, you could identify sentences that these terms appear in and have an expert annotate a sample of these sentences and candidates terms to solidify a label set. This targeted approach reduces the time and effort spent annotating an initial labeled set. Once an initial set of entity tags is established, similar terms can be assigned labels based on their cosine similarity to generate more distantly supervised labeled data. You could get sophisticated here and use Snorkel to define some labeling functions to scale up your annotations.

In the latter case, you could cluster these candidate terms and use the word closest to the cluster centroid as the entity label. This is sure to be a messy process but it’s worth an experiment to see if the results are at all useful, especially since this requires essentially no human oversight.

Again, you can use this labeled data to train a sequence classifier to tag entities. One drawback of this approach is that most of these methods (e.g. TF-IDF, Word2vec, etc.) operate at the token level and as such, will only generate single token candidates. Luckily, manually annotated data from the domain expert will alleviate this to some extent. Further heuristics can probably be employed, such as noun phrase detection, to overcome this drawback in the fully unsupervised setting.

There are plenty of other hybrid approaches to explore that involve transfer learning from a pre-trained model, pre-training word embeddings using your domain-specific corpus for use in the sequence model, and active learning. Additionally, there is much to be said about feature engineering for the sequence classifier.

With respect to evaluation, we naturally will want to hold out a test set to evaluate any model trained. Precision, recall, and \(F_1\) score are all relevant here though it should be noted that there are some difficulties with evaluating a system that is trained at the word level but evaluated at the entity level (i.e. potentially multiple words).

I may start testing out some of the ideas described above and revise this post as I learn more. Future posts will discuss relation extraction and reasoning tasks.

Leave a comment