MLOps Tooling

TLDR; I recently attended the MLOps NYC conference, where I explored some neat new tools for building and managing machine learning models.

Anyone in the industry knows how confusing it can be to discern between a data scientist, data engineer, model ops engineer, research scientist, and the list goes on. Titles aside, getting models into production (i.e. serving a ML model that provides predictions) is frankly where the money is. Models don’t drive metrics by sitting in a jupyter notebook on a laptop. However, going from a pickle file or .h5 file to a CICD pipeline that you can rely on for rapid model updates is a huge lift. Everyone always points to this Google paper to explain the complexity of deploying machine learning models. The topic of the conference should now be clear. The goal is to develop pipelines that allow you to train and deploy models in a robust, repeatable, and automated fashion.

I went to the training track, which covered Kubeflow, MLFlow, SageMaker, and a number of other bespoke tools. I also discovered Dask and Rapids while I was there. I’ll attempt to give a quick overview of each of these tools.

Kubeflow

Kubeflow is Google’s open source framework for managing model training and deployments on Kubernetes. It comes with a full suite of tooling that you would need for a production grade system such as logged training runs, complex training job management (e.g. execution graphs to prepare training data, train the model, test the model, etc.), hyperparameter optimization tooling, and model serving infrastructure. This is all amazing stuff. It runs on top of Kubernetes so you get the benefit of creating scalable microservices (e.g. model servers) and running complex training jobs that can be parallelized across many worker nodes.

All of this comes at a cost, however. Managing a Kubernetes cluster running Kubeflow is a full time job. There are many layers of abstraction to wade through before you can really be productive with this toolchain. In my opininion, it takes a deep knowledge of Kubernetes and a deep understanding of what each of the tools in Kubeflow does. For example, understanding Kubeflow components such as Katib, TFJob, KFServing, and Pipelines is not trivial. Add in the need to understand what infrastructure requirements you have and how to minimize costs (e.g. scalable GPU node pools, etc.). Layer in the brutality of writing YAML files and I could understand why a data scientist would be put off by the whole endeavor. Here’s an example TFJob YAML file.

apiVersion: kubeflow.org/v1

kind: TFJob

metadata:

generateName: tfjob

namespace: kubeflow

spec:

tfReplicaSpecs:

PS:

replicas: 1

restartPolicy: OnFailure

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: tensorflow

image: gcr.io/your-project/your-image

command:

- python

- -m

- trainer.task

- --batch_size=32

- --training_steps=1000

env:

- name: GOOGLE_APPLICATION_CREDENTIALS

value: "/etc/secrets/user-gcp-sa.json"

volumeMounts:

- name: sa

mountPath: "/etc/secrets"

readOnly: true

volumes:

- name: sa

secret:

secretName: user-gcp-sa

Worker:

replicas: 1

restartPolicy: OnFailure

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: tensorflow

image: gcr.io/your-project/your-image

command:

- python

- -m

- trainer.task

- --batch_size=32

- --training_steps=1000

env:

- name: GOOGLE_APPLICATION_CREDENTIALS

value: "/etc/secrets/user-gcp-sa.json"

volumeMounts:

- name: sa

mountPath: "/etc/secrets"

readOnly: true

volumes:

- name: sa

secret:

secretName: user-gcp-saI have been tinkering with Kubeflow since the earliest versions were released on Github and one positive development is that it has gotten easier to deploy Kubeflow. I still haven’t used it to productionize a model 1) due to the complexity of the system and 2) much of my work tends to be much more exploratory in nature. I still don’t think we’ve converged on the final version of this toolchain but Kubeflow and Google’s support are certainly exciting developments in the ecosystem.

MLFlow

MLFlow is Databricks’s open source framework for managing machine learning models “including experimentation, reproducibility and deployment.” MLFlow feels much lighter weight than Kubeflow and depending on what you’re trying to accomplish that could be a great thing. MLFlow feels a little more approachable as a data scientist since the focus is mainly on recording experimental runs and comparing results, with very little extra code. See the extra code for a typical Sklearn model run below.

with mlflow.start_run():

lr = ElasticNet(alpha=alpha, l1_ratio=l1_ratio, random_state=42)

lr.fit(train_x, train_y)

predicted_qualities = lr.predict(test_x)

(rmse, mae, r2) = eval_metrics(test_y, predicted_qualities)

print("Elasticnet model (alpha=%f, l1_ratio=%f):" % (alpha, l1_ratio))

print(" RMSE: %s" % rmse)

print(" MAE: %s" % mae)

print(" R2: %s" % r2)

mlflow.log_param("alpha", alpha)

mlflow.log_param("l1_ratio", l1_ratio)

mlflow.log_metric("rmse", rmse)

mlflow.log_metric("r2", r2)

mlflow.log_metric("mae", mae)

mlflow.sklearn.log_model(lr, "model")Then once you have the model that you like you can deploy with very little code such as:

mlflow models serve -m /Users/mlflow/mlflow-prototype/mlruns/0/run_id/artifacts/model -p 1234

There is still the challenge of infrastructure so someone will have to sort that out but at least the experimentation and logging has been handled by a relatively lightweight bolt-on system that data scientists won’t object to using.

SageMaker

SageMaker is AWS’s fully managed suite of tools to train and deploy machine learning models. AWS has done a terrific job making the lives of developers easier. This is probably the easiest of all the toolchains given that there is a tight coupling of training jobs, model serving, and infrastructure. Much of it is abstracted away from the user and that has its pros and cons. On the one hand you don’t have to really think about infrastructure for training or deployment but on the other hand, you may not have as fine-grained control as you might like to run bandit experiments, etc.

SageMaker offers up a number of commonly used ML algos and also allows you to bring your own Docker images to run your training jobs. Another very cool thing to highlight with SageMaker is active learning, which is a way to bootstrap an ML model with as few training data points as possible and rapidly improve the model with the data points that will improve the model the most.

Dask

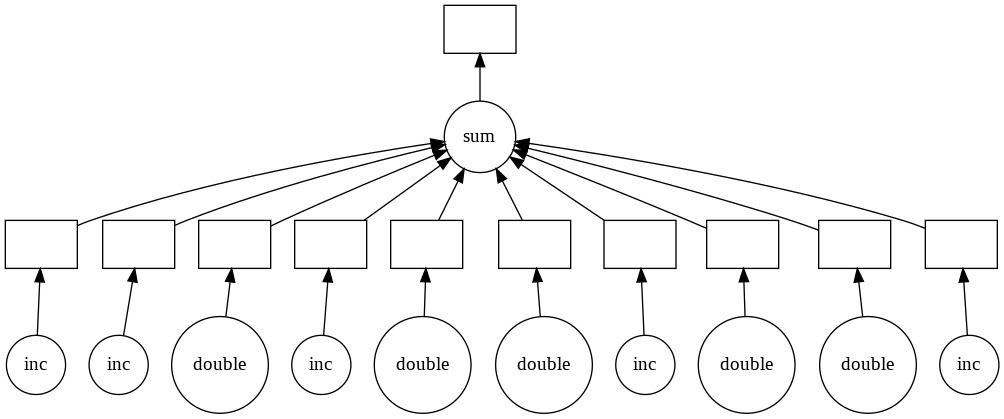

While not a tool for managing deployed machine learning models, dask is a nice addition to any data scientist’s toolbelt. Dask is a framework that allows data scientists to run ML models, apply functions to Pandas dataframes, among many other things, in a highly parallelizable fashion. For anyone that has used multiprocessing to utilize all your CPU-cores, this will make a lot of sense. Dask is a DAG engine and it even shows you what it’s doing under the hood with these neat visuals.

Naturally, you might be asking yourself, doesn’t Spark do that? At least that was the first question that came to my mind, having worked with Spark extensively. It turns out that it’s the right question to ask, so much so that there is an entire page dedicated to it. The verdict: Dask is much lighter weight than Spark and is the logical starting point for a lot of data science related parallelization tasks. However, everything you learned in Spark will help you here. All the lazy evaluation, sampling the first few rows of the dataset to infer datatypes (and pulling your hair out to get dtypes correct), thinking about how to partition your dataset, figuring out when to persist data in memory, using columnar storage like Parquet to optimize your reads, etc. The two libaries even have a fairly similar ML model API.

As I finish writing this paragraph, I’m sort of scratching my head thinking, gee, this really does seem EXACTLY like Spark.

The upshot of Dask is that you can operate on datasets that are much larger than memory (e.g. 100gb) by operating on chunks of the dataset. Further, you can use APIs that look and feel a lot like Numpy and Pandas. You can operate in cluster mode and harness the power of 1000’s of CPU cores and they claim the scheduler is up for the task (“task” - pun intended). I’m certainly going to check out Dask-Kubernetes, as it has the ability to scale the number of workers you have dynamically based on workload. I can see two obvious cases where this would be very useful: 1) for grid search, and 2) serving online models (e.g. fit a KMeans model on incoming data).

The downside is that dask hasn’t and won’t implement certain things. Here it is, straight from the horse’s mouth.

Dask Limitations

Dask.array does not implement the entire numpy interface. Users expecting this will be disappointed. Notably dask.array has the following failings:

- Dask does not implement all of

np.linalg. This has been done by a number of excellent BLAS/LAPACK implementations and is the focus of numerous ongoing academic research projects. - Dask.array does not support any operation where the resulting shape

depends on the values of the array. In order to form the Dask graph we

must be able to infer the shape of the array before actually executing the

operation. This precludes operations like indexing one Dask array with

another or operations like

np.where. - Dask.array does not attempt operations like

sortwhich are notoriously difficult to do in parallel and are of somewhat diminished value on very large data (you rarely actually need a full sort). Often we include parallel-friendly alternatives liketopk. - Dask development is driven by immediate need, and so many lesser used

functions, like

np.full_likehave not been implemented purely out of laziness. These would make excellent community contributions.

Dask.dataframe only covers a small but well-used portion of the Pandas API. This limitation is for two reasons:

- The Pandas API is huge

- Some operations are genuinely hard to do in parallel (e.g. sort) [Todd’s note: I encountered this going through their tutorial. Series.sort_values just didn’t exist. Sad panda.]

Additionally, some important operations like set_index work, but are slower

than in Pandas because they include substantial shuffling of data, and may write out to disk.

Dask is very powerful on its own and I intend to start using it for basic data preparation tasks on large datasets (e.g. a Twitter dataset of a billion newline delimited JSON Tweets). However, we won’t stop here with Dask. Enter Rapids.

Rapids

RAPIDS is NVIDIA’s open source GPU accelerated library for dataframes, classic ML algos, and graph algos. NVIDIA gave a talk at the MLOps conference describing this work and it seems tremendously promising. The tooling here is still under very active development but they’re using Dask in a couple neat ways: 1) to scale their cuDF library across multiple GPUs and 2) to scale ML model development across multiple GPUs. Of course, TF and PyTorch have been using GPUs (and even multiple GPUs) for years now, however, this is the first time I’ve seen support for the classic ML agos like K-Means and Random Forest on GPUs. This is a brilliant marketing strategy for NVIDIA. They’re introducing an “open source” library that only runs on their proprietary GPUs. If you want the “free” software, you have to pay for their hardware. It will be interesting to see if the TPU can offer something similar.

Again, there is a long laundry list of asterisks associated with the current version of the tooling, namely that they can’t mimic the Pandas API due some of the reasons cited above. If you want to check out their APIs there are some great resources here.

I will certainly be checking out RAPIDS for some of my lighter-weight modeling tasks or even for the online learning scenario that I described above. I have a web app that needs to run K-Means on the fly. I need to search for the optimal number of clusters, K, so I grid search through some reasonable hyperparameters and present the clustering results. That takes time and a user wants results basically instantaneously so if you can reduce the wait time from 20 seconds down to 1 second, you’ve meaningfully improved the user experience.

Closing Thoughts

Many of the presenters at the MLOps Conference spoke as if model deployments could/should be managed by data scientists. In my opinion, model operations engineering really is a full-time job that is separate from data science. There is a clear division of responsibilities. Data scientists/research scientists are responsible for defining model architectures, designing experiments, and finding optimal hyperparameters. Model operations engineers (DevOps counterparts for the ML ecosystem) are responsible for ensuring that models can be rapidly deployed, models are performant, serving infrastructure is scalable, and that models are always live. There are so many other tasks in here that may or may not fall on the model operations engineers as well such as AB testing and administration of the cluster.

What do you think? Leave a comment at the link below.

Leave a comment